AMERICANLAWN

SURFACEOFEVERYDAYLIFE

The American Lawn: Surface of Everyday Life traces the evolution of the lawn from its British antecedents to the development of the American suburb and the present-day eco-politics of the “freedom lawn.” The multimedia exhibition portrays the lawn as both a benign platform of controlled domestic growth and a sinister surface of repressed horror. Historic and contemporary materials drawn from high culture as well as popular culture demonstrate that there is more to that simple carpet of grass than meets the eye.

The lawn is anything but natural. It is a patented, engineered product, subjected to the laws of industry and genetic science. Hundreds of grass cultivars are bred for color, texture, density, and longevity while lawn diseases and their patterns of behavior are studied in order to breed preternaturally healthy, disease-resistant species. A primary objective of turfgrass research and engineering is to develop a superspecies that thrives in all conditions.

In a gallery focusing on “Engineering the Lawn,” a vitrine displays freeze-dried samples of various grass cultivars back-to-back with varieties of Astroturf, which, like natural grasses, are engineered to achieve precise performance specifications that determine weave, density, texture, fiber strength, and blade length. In the same space, an inventory of weeds and blemishes is presented opposite a collection of turfgrass patents. Since the nineteenth century, the pervasive use of lawns in the landscaping of governmental, religious, and cultural buildings has made the lawn synonymous with both collective solidarity and institutional power. The federal lawn, for example, is a strategic symbol of political unity, indispensable to representations of American democracy in broadcast media. In a section on the “Power Lawn,” a series of video monitors show the White House’s North Lawn as a backdrop for public protests; the South Lawn is used to stage treaty signings and national ceremonies, its helicopter landing zone dramatizing the arrival and departure of presidents; and the lawn of the National Mall is a site for large demonstrations and marches. In the same gallery, Ezra Stoller’s iconic black-and-white photographs of 1960s corporate headquarters depict well-groomed suburban lawns exploded to a monumental scale. These unpopulated spaces function as both sanitized aesthetic frames for heroic Modernist architecture and as perimeter zones of surveillance.

In American domestic culture, the lawn is a battleground between the democratic image of uniformity and the right to self-expression guaranteed by the First Amendment. Mowing, for example, is an important civic duty. The preservation of a two-inch-high verdant pile is at once the common bond between happy neighbors conforming to an unwritten social contract and a competitive battlefield on which individual rivalries are displayed side by side. Lining the walls of the gallery titled “Decoding the Lawn,” Robert Sansone’s photos of contested property lines between neighboring lawns are displayed in stereoscopic viewers. Projected on the floor are texts excerpted from lawn-related lawsuits involving obligations to mow and weed, civil liability, the right to display signage, cross burning, and guaranteed access for postal workers.

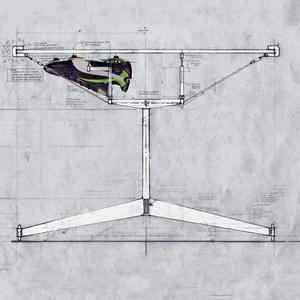

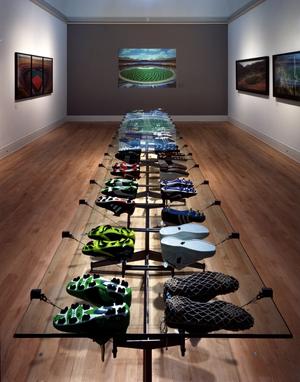

Since the late 1800s, sports have been the driving force behind the research and development of turfgrass technologies — now a multibillion-dollar industry. Golf, baseball, football, and soccer demand distinct lawns that satisfy each sport’s particular requirements of durability, bounce, and speed, which have in turn led to the development of sports shoes. Cleat shape, construction, and materials have been biomechanically engineered to respond to the torsional and kinetic demands of each sport and its playing surface. A display case for thirty-two pairs of athletic shoes for a variety of sports occupies the center of the gallery focused on the “Competitive Lawn.” The protective glass surface of the case is supported by the cleated soles of the upturned shoes. Beyond, photographs of stadium mowing patterns are projected on one wall: intricate plaids, swirls, and sunburst motifs created by groundskeeper David Mellor to animate the playing surface at the Boston Red Sox’s Fenway Park, and driven by demands from sports broadcasters to make turfgrass more telegenic than ordinary grass.

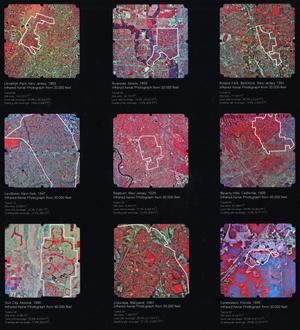

Also on display is a video that follows the metronomic oscillation of a lawn sprinkler watering two neighboring front yards and exposing real-time vignettes of everyday scenes of suburbia; infrared photographs and maquettes of nine significant American suburbs; and film clips from popular films such as David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986) and John Carpenter’s Halloween (1978).

Outside, the museum lawn talks to you. Speakers in the grass utter solicitations to passersby: “Touch me. Caress me. Walk all over me. Moisten my shoots. Run your fingers through my blades. Sit on me. Pamper me. Inhale my aroma. Dominate me.” Nearby, artist Mel Ziegler has mowed a “grass relief” that records an estimated tally of the lawn’s blades of grass: 325,293,680.

The American Lawn: Surface of Everyday Life was curated in collaboration with Georges Teyssot, Beatriz Colomina, Mark Wigley, and Alessandra Ponte. The exhibition complements the book by the same title.

| opening16th June 1998 | closed8th November 1998 | opening4th April 1999 |

| closed7th June 1999 | opening3rd September 1999 | closed2nd January 2000 |

| Opening4th April 1999 | Closed7th June 1999 |

| Team | Elizabeth Diller,Ricardo Scofidio,Mark Wasiuta,Lyn Rice,and Gwynne Keathley |

| Project Director / Associate Curator | Mark Wasiuta |

| Curators | Georges Teyssot,Beatriz Colomina,Mark Wigley,and Alessandra Ponte |

| Researcher | Gwynne Keathley |