THEROTARYNOTARYANDHISHOTPLATE

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even, also known as The Large Glass, is the point of origin and point of departure for a crossover theater work conceived for Apropos of Marcel Duchamp 1887/1987, a centennial celebration of the artist organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Duchamp developed his seminal work between 1915 and 1923, constructing it from two stacked glass panels and nontraditional materials such as oil, varnish, lead foil, lead wire, and dust. The work is not hung on a wall; it is free-standing and meant to be seen from all sides.

What has become an icon of twentieth-century art is, arguably, the most iconoclastic work of its time. Poet and essayist Octavio Paz said that The Large Glass is about the myth of criticism—criticism being the only truly modern idea. Interpreted as an attack on the syntactic condition of painting, The Large Glass is often compared to James Joyce’s experimental novel Finnegans Wake (1939) and is documented in years of Duchamp’s sketches and notes. The theatrical work The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate was shaped by a self-imposed mandate to find a point of equilibrium between fidelity and irreverence toward the Large Glass.

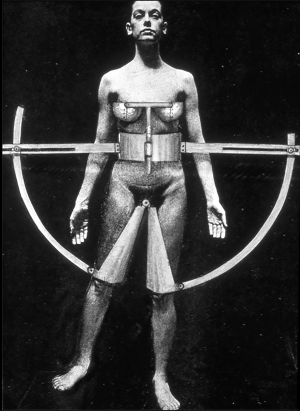

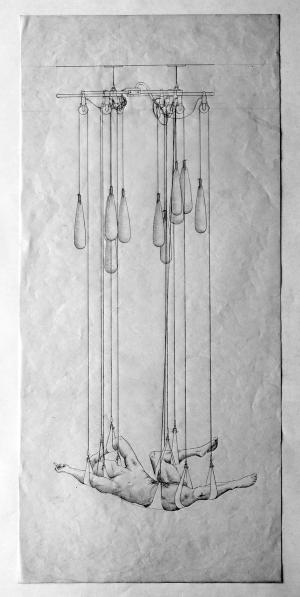

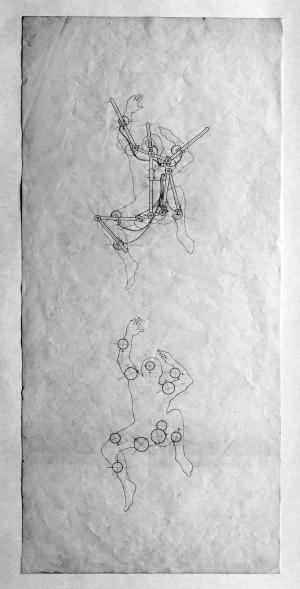

The iconography of The Large Glass is reduced to seven animated components, four of them human: the Field, the Apparatus, the Mechanical Bed, the Bride, the Bachelor, the Witness, and the Juggler. The structure of the work is a circuitous anti-narrative whose objective is irreconcilability. Visual and textual languages are simultaneous and sometimes coincidental.

Rotary Notary subverts the space of the stage in much the way that The Large Glass subverts the space of painting and sculpture. In contrast to the theater of illusion—in which a proscenium divides the narrative space of the stage from the audience—the piece’s “interscenium” offers a splintered view of the stage that is both illusionistic and analytical.

The performance space is neutral, with no elevated stage, no frame, and no wings. An opaque pivoting panel splits the stage in two: downstage for the Bride, and upstage for the Bachelor. When the front half is revealed, the back is obscured. A rotation of 180 degrees exchanges the domains of Bride and Bachelor like a revolving door. A mirror suspended at a forty-five-degree angle above the stage reflects what the audience cannot see behind the panel, but reoriented to a right angle. As a result, the audience sees half the stage from a typical frontal perspective and the other half in plan, as a reflection in the mirror. When one character is seen actually, the other is seen virtually.

The characters continually exchange locations, physical states, and sexual identities in a game of temptation and denial. The Mechanical Bed is positioned so that the headboard allows the audience to see the performer’s head actually and his body virtually, reflected in plan view. The body and head sometimes cooperate and at other times split into two characters—a headless body reciting commands to a bodiless head that sometimes obeys.

| Location Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, United States |

| performed22nd September 1987 | closed25th September 1987 | performed29th September 1987 |

| closed2nd October 1987 |

| Team | Elizabeth Diller,Ricardo Scofidio,Christopher Otterbine,and John Gunderson |

| Susan Mosakowski | Writer and Director |

| Vito Ricci | Music |

| Pat Dignan | Lighting Design |

| Richard Curtis | Costumes & Objects |