BLURBUILDING

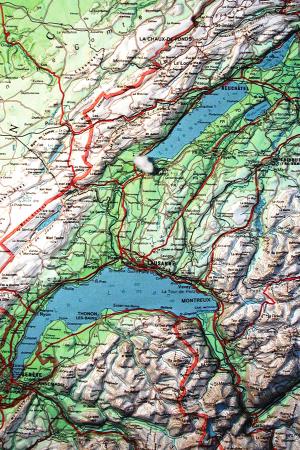

SWISSEXPO2002,YVERDON-LES-BAINS,SWITZERLAND

To blur means to make indistinct, to dim, to shroud, to cloud, to make vague, to obfuscate. Blurring is often associated with error: A malfunctioning camera produces a blurred image. Blurred vision is considered a visual impairment. There are, however, positive ways to think about blur. Motion blur was a technique used by Futurist photographers who sought to express physical movement in space. Blurring is a standard feature in image-editing software. Camera lenses in Japan are rated according to blur coherence, or bokeh. Blur, built for the Swiss National Exposition in 2002, was conceived to be out of focus, a response to the oversaturation of visual media in expositions that had become showcases filled with spectacular state-of-the-art immersion technologies and digital simulations. These displays of technical prowess fed an insatiable appetite for visual stimulation with ever-greater virtuosity in a society with a consumer culture that measured satisfaction in pixels per inch. High definition had become the new orthodoxy. By contrast, Blur’s atomized water environment was low definition—an architecture of atmosphere.

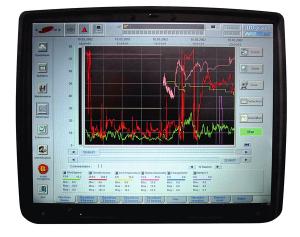

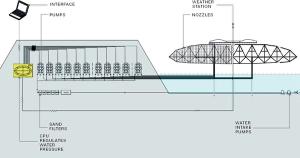

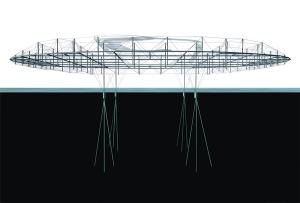

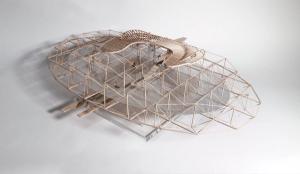

The three-hundred-foot-wide, two-hundred-foot-deep, seventy-five-foot-high lightweight tensegrity structure was supported on the lake bed by four columns. The open-air platform offered nothing to see or do but contemplate our dependence on vision itself. It was an experiment in de-emphasis on an environmental scale. Fresh water was pumped from Lake Neuchâtel, filtered, and shot as a fine mist through thirty-five thousand high-pressure nozzles. The resulting fog mass changed from season to season, day to day, hour to hour, and minute to minute in a continuous dynamic display of natural versus man-made forces. Blur was unpredictable yet had certain tendencies: high winds revealed the leading edge of the structure and produced long fog trails; high humidity and high temperatures expanded the fog outward; high humidity and cool temperatures made the fog fall to the lake and roll outward; low humidity and high temperatures had an evaporating effect; air temperature cooler than the lake temperature produced a convection current that lifted the fog upward. A smart weather system tracked the shifting climatic conditions of temperature, humidity, and wind, regulating water pressure in various zones to maintain the fog mass. The system learned how to behave over time; it was a primitive form of artificial intelligence.

Visitors crossed a long ramp from shore and ascended a stairway to a platform where all visual and acoustic references were erased. There was only an optical whiteout and the white noise of hissing nozzles. Entering Blur was like stepping into a habitable medium, one that was formless, featureless, depthless, scaleless, massless, surfaceless, and dimensionless. On the platform, movement was unregulated, and the public was free to wander through the fog bank. One could ascend to the upper-level Angel Deck via a stairway that broke through the fog into the blue sky, like piercing a cloud layer in flight.

Water was not only Blur’s context and primary building material but also a gustatory pleasure. The Water Bar, submerged one-half level below the upper deck, offered a broad selection of bottled waters, including spring water, artesian water, mineral water, sparkling water, and distilled water from around the world, an array that could satisfy the most discerning connoisseur. The public was invited to drink the building. Soon after Blur opened, it was immortalized in a souvenir chocolate bar, a uniquely Swiss form of commemoration. The public could eat the building too.

Weather scientists, water engineers, structural engineers, agricultural experts, scuba divers, mountain climbers, a novelist, and a sound artist contributed to the pavilion’s realization. Christian Marclay created subtle acoustic effects within.

Despite the town’s interest in converting the pavilion into a science fiction museum, the temporary structure was taken apart six months after the exposition closed, restoring the lake to its original state and recycling its steel for new structural profiles.

| Size (GSF) | 80000 | Location | Swiss Expo 2002, Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland |

| Commission1998 | opening15th May 2002 | closed20th October 2002 |

| Partners | Elizabeth Diller and Ricardo Scofidio |

| Project Leaders | Dirk Hebel,Lyn Rice,and Charles Renfro |

| Designers | Eric Bunge,Reto Geiser,David Huang,Karin Ocker,Andreas Quadenau,Deane Simpson,Matthew Johnson,Nicholas de Monechaux,and Alex Haw |

| Passera & Pedretti | Structural Engineer |

| Riesen Ingenieure | Mechanical Engineer |

| Bering AG | Electrical Engineer |

| Delux | Lighting Designer |

| Biogenesis, Dutrie, Mee Industries, & Processing Art | Fog System |

| Glasconsult | Glass Engineer |

| Meteo Suisse | Meteorologist |

| Pareth Engineers | Structural Engineers (Log-in Station) |

| Haslinger Stahlbau | Steel Structure |

| CSA | Environmental Consultant |

| Stellavista and Action Media Technologies | LEDS Consultant |

| Staubli, Kurath & Partners, Swissfiber, Inflate, Fiberoptic | Special Materials Consultant |

| Christian Marclay | External Artist |

| Fujiko Nakaya | Advisor |

| HRS | General Contractor |