BRAINCOAT

Vision typically dominates our behavior in public and establishes the basis of social relations. We rely on vision to assess identity: a quick glimpse of another person allows us to infer his or her sex, age, race, and social class. Under normal conditions, this visual assessment precedes any social interaction. But the Blur Building’s fogbank produces a condition of anonymity: it is difficult to distinguish a twenty-five-year-old Japanese fashion model from a thirteen-year-old Indian boy or a seventy-year-old Russian grandmother. Braincoat is an experiment on interpersonal communication within a space of compromised perception: vision is blurred by the fog, and hearing is dulled by the pervasive white noise of hissing water nozzles.

Braincoat does not rely on language, either spoken or written. The project introduces the notion of “proxi-communications,” a telecommunications network recalibrated to human scale and used to augment the information we glean from our immediate surroundings. Because Blur deprives visitors of the visual clues typically used to gauge the physical environment and the social relations within it, the braincoat—a prosthetic skin in the form of a raincoat with embedded technologies—allows visitors to gain a sixth sense. This new form of “social radar” produces a condition of anonymous intimacy.

Visual cues—in the form of facial expressions, body language, blanching, and blushing, among other reactions—hold great communicative power, particularly when conventional language fails. Thus nonverbal expression suggests the potential for wearable technologies. What if wireless communications acquired the intelligence to transmit emotions, thoughts, personal attraction, aversion, and even embarrassment?

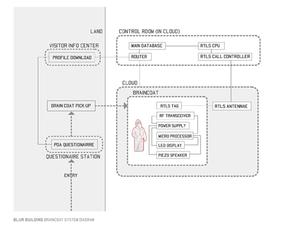

All visitors enter Blur at a log-in station located at the base of the entrance ramp. Each visitor completes a questionnaire while waiting in the entry queue. The answers are used to produce a unique profile that is added to a cumulative database. Each visitor is then issued a braincoat that includes an imprint of his or her profile, enabling the coats to communicate with one another. The basis for this communication is the database, a data cloud that complements the fog cloud.

The questionnaire is an integral part of the creative project and was conceived in collaboration with fiction writer Douglas Cooper. Although each visitor responds to only twenty questions, these are randomly culled from a set of several hundred questions. With the aid of a data-clustering program used to create internet marketing profiles, visitors’ answers are compared and evaluated by establishing correlations among the entire range of questions.

The braincoats have the capacity to display three types of response. First, a visual response: as visitors pass one another, their coats compare character profiles and change color to indicate their degree of affinity, much like an involuntary blush. When stimulated, the chest panel of the translucent braincoat displays a diffuse colored light that glows in the fog. The coat functions as a sophisticated Lovegety—a handheld matchmaking gadget popular with Japanese teenagers in the late 1990s. The color range is coded: a warm red tone indicates affinity while a cool blue-green hue signifies antipathy. The degree of color shift intensifies in proportion to the strength of the reaction.

Second, the coat renders an acoustic response: a statistical match triggers an audible pulse, like sonar, from a speaker embedded in the coat, audible only to the wearer. As matched visitors approach each other, the steady pulse accelerates, reaching a peak when the two are very near. Using this social sonar, visitors can choose how to navigate, either avoiding encounters, tracking their best matches, or remaining indifferent.

Third, there is a tactile response: occasionally, two visitors may have a 100 percent affinity. To register this rare occurrence, a small vibrating pad—modeled after the vibrating motor of a pager—is located in a rear pocket of the braincoat. When two perfectly matched visitors encounter each other in the fog, the motors in their respective coats send vibrations to the buttocks—mimicking the tingle of excitement that comes with physical attraction.

The technical realization of the Braincoat was a collaboration with IDEO of Palo Alto, California. The research lost its funding when the project sponsor, a telecommunications company, fell victim to a corporate takeover. The project predated the arrival of widely popular location-based dating apps, such as Grindr, which was launched in 2009, and Tinder, which followed in 2012.

Chest panel of the braincoat displays a diffused colored light

Chest panel of the braincoat displays a diffused colored light Visual communications

Visual communications Log-in / Log-out sequence

Log-in / Log-out sequence

| Location Swiss Expo 2002, Yverdon-les-Bains, Switzerland |

| Team | Elizabeth Diller,Ricardo Scofidio,Matthew Johnson,Mark Wasiuta,Dirk Hebel,and Nicholas de Monechaux |

| Ben Rubin + Tom Igo | Collaborators |

| EAR Studio | Engineering |

| Douglas Cooper | Writer |

| IDEO Company | Research + Development |