BADPRESS

DISSIDENTIRONING

Efficiency infiltrated the domestic sphere in the first years of the twentieth century. In 1913, soon after American engineer Frank Gilbreth improved the efficiency of bricklaying by minimizing a mason’s need to bend and stoop, the pioneering home economist Christine Frederick asked, “Didn’t I, with hundreds of women, stoop unnecessarily over kitchen tables, sinks and ironing boards, as bricklayers stoop over bricks?” Domestic efficiency found its modern spatial expression in Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s compact Frankfurt Kitchen (1926), designed to save time, space, money, and human energy. The drive toward household efficiency ushered in an army of new household appliances — so-called electric servants — that promised to liberate the housebound wife and enable her to join the labor force. But in practice, gains in efficiency only gave rise to greater domestic workloads.

By the middle of the century, the typical American home had grown and was increasingly stuffed with cutting-edge household appliances. Sold on promises of convenience and cleanliness, these new gadgets required continual maintenance and periodic replacement in the wake of obsolescence. As the home was remade in the image of modern efficiency, its ideals began to be impressed upon the female body as well. Like the latest gadget, it should exhibit no signs of decay but reflect a state of order. These parallel projects were dedicated to preventing the corrosions of age and to the daily restoration of an ideal whose standards were produced and sustained in popular media. Today, the maintenance of the home and the body have found a new conjunction: household chores can be incorporated into a daily aerobic regimen and performed to the beat of a streaming fitness video. At the same time, the prerogatives of housework — dirt management and the daily restoration of order — never strayed far from the economic ethos of industry.

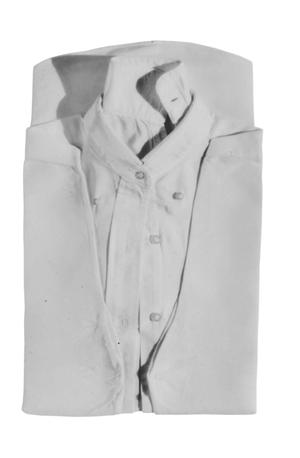

Bad Press examines ironing in relation to the cult of efficiency and the domesticated body. The chore of ironing is governed by minimums. The standardized ironing pattern for a man’s shirt, for instance, always returns the garment to a flat, rectangular shape. A minimum of effort is used to reshape the shirt into a two-dimensional form with minimal folds or creases. It yields a repetitive unit that will consume as little space as possible, fitting economically into orthogonal systems of storage. At the site of manufacture, the factory-pressed shirt is stacked and packed into rectangular cartons that are loaded as cubic volume onto trucks and transported to retail shops, where the shirt’s form is reinforced in rectangular display cases. After purchase, the pressed shirt’s rectangular form is sustained at home — stowed in dresser drawers or on closet shelves — and away from home, packed in suitcases. The shirt is disciplined at every stage to conform to efficient storage.

When the shirt is worn, the residue of the orthogonal logic of efficiency registers on the surface of the body. The parallel creases and crisp, square corners of a clean, pressed shirt have become sought-after emblems of refinement. The byproduct of efficiency has become a new object of desire. But what if the practice of ironing could be freed from the aesthetics of efficiency altogether? Perhaps ironing could more aptly represent the postindustrial body by trading the image of the functional for that of the dysfunctional.

Bad Press divorced the task of ironing from the aesthetics of efficiency by exploring labor-intensive patterns that resulted in unexpected alternatives for folding, buttoning, and pressing a man’s shirt; this produced shirts in a state that could not be stacked or packed.

A practice of dissident ironing, if relieved from the burdens of propriety, could, perhaps, evolve new codes. Consider, for example, the covert language developed by prison inmates assigned to laundry detail. Seemingly superfluous decorative creases pressed into prison uniforms are invested with representational value, a system of ciphers recognizable solely to the inmates. Like the prison tattoo, the crease has become another mark of resistance by a marginalized population. But whereas the tattoo acts directly on the skin — the inmate’s sole possession — the crease acts on the institutional skin of the prison uniform. Its defacement is made all the more subversive in its camouflage: the crease is illegible to the uninitiated. The articulations produced by a practice of dissident ironing similarly reprogram codes of efficiency to broadcast other messages.

Bad Press was first exhibited at the Centre d’art contemporain in Castres, France, with later iterations shown at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum in New York, the MAXXI in Rome, and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

Standard folded shirt

Standard folded shirt Lapel fold with crumpled panels

Lapel fold with crumpled panels Rolled shirt in sleeve

Rolled shirt in sleeve

| Location SFMoMA, San Francisco, United States |

| opening21st April 1993 | closed23rd June 1993 | opening18th November 1993 |

| closed19th December 1993 |

| Team | Elizabeth Diller,Ricardo Scofidio,John Bachus,Brendan Cotter,Heather Champ,and David Lindberg |